The Sermon That Birthed a President: Nnamdi Azikiwe’s Reflections on Christianity

The Sermon That Birthed a President: Nnamdi Azikiwe’s Reflections on Christianity

Written by Nathalie Agbessi

139 Bamgboshe Street. The windows flung wide open to ease the suffocating heat of a sweltering morning. The scent of fried yam from the street vendor perfumes the narrow lane. A cyclist shouts at the children playing football with a mango pit, urging them to clear the path. Further down, the church bell rang, a call to worship, a reminder for those like Nnamdi Azikiwe (Zik), who were still en route, that the service was about to begin. Dressed in his Sunday best, a white short-sleeved shirt, khaki shorts, and a brown pair of boots freshly gifted by his father in recognition of his excellent performance at school, Zik walked at a brisk pace, eager not to miss the most out of the day’s sermon.

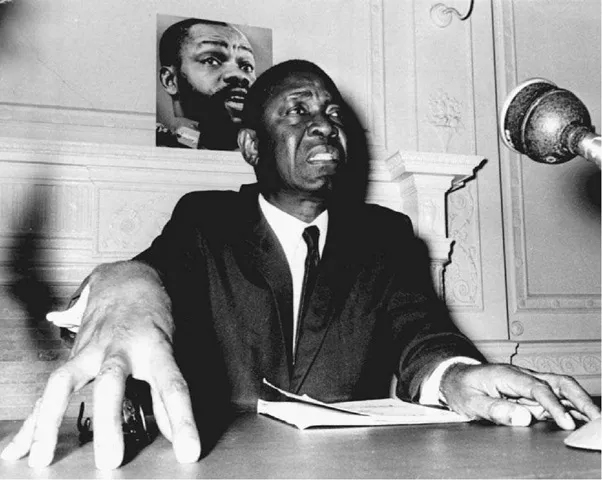

Later that Sunday, a veil would be lifted from Azikiwe’s eyes. Not by a direct encounter with Christ but through the preaching of the Ghanaian educator Dr. Kwegyir Aggrey. That morning, Kwegyir’s sermon, inspired by Isaiah 6:1-10, ignited a spiritual awakening that would later evolve into a political calling in the young Zik. In his autobiography, My Odyssey, Nnamdi Azikiwe recalls that Kwegyir on that Sunday preached as a prophet, and as if he “had come to announce the glad tidings that ‘Nothing but the best is good enough for Africa.'”1

Like many African intellectuals of the same generation who received missionary education and grew up in Christian homes, Nnamdi Azikiwe’s thought was deeply shaped by Christianity. From boyhood, his worldview was grounded in a strong ethical commitment to Christian ideals, such as the belief that all humans are created in the image of God and that human dignity is inherent to every human being. These beliefs would later be expressed in his political philosophy, commonly known as Zikism, through its emphasis on universal brotherhood and fatherhood, which entails service to others, equality, mutual care, and a shared sense of Humanity that transcended race, nationality, and ethnicity.

The influence of Christian ideals on Zik’s worldview and thinking is particularly evident in Renascent Africa. In this important work, Christian imagery and language are deployed to articulate political ideas. For example, Zik believes that one of the core teachings of Christianity is the cultivation of a rich and meaningful life here on earth rather than the pursuit of eternal life after death. In fact, he claims that the Christian New Jerusalem is not a “heavenly city” but “a philosophic concept,” a vision of the world as a State that requires rebirth2.

Azikiwe’s engagement with Christianity was pragmatic. He viewed the teachings of Jesus in parallel with those of the ancient Greek sage Socrates. The immortality of these two figures, particularly Jesus, according to Azikiwe, stems from an enduring commitment to Humanity rather than a supernatural resurrection. In his view, both Jesus and Socrates were social reformers who transcended time through their devotion to the betterment of humankind and their dedication to the welfare of Humanity and its most destitute elements, a cause Jesus was remarkably invested in. Eternity, therefore, for Zik, isn’t a perpetuation of life after death but a state that he himself was set on achieving through the fulfillment of his own calling, as he states in Renaissance Africa: “My destiny is before me. I march towards it full of hope and courage. Life is an empty dream, and once my task has been done, the wide expanse of eternity is my ultimate destiny. But if, like Socrates, Jesus, and Paul, I go the way of the flesh, I will continue the march!”3.

Eternity in Azikiwe’s thought wasn’t only reserved just for the likes of Socrates, Paul, or Jesus but for any Human being who dares to fulfill their destiny by living in service to Humanity or by committing their existence on earth to what Azikiwe considers to be the essential message of Christianity: universal fatherhood and brotherhood. In fact, Azikiwe affirmed that the true encounter with life takes place here on earth and considered anyone who believes that this meeting can only occur after death doomed. For him, building a modern Africa demanded more than political reform. It required a spiritual shift in mentality that could be inspired by Christian ethics, which prompted his own spiritual-political awakening at Tinubu Methodist Church.

Despite his appreciation for the moral core of Christianity, Azikiwe was unflinching in his critique of the African religious elite. Rather than making Humanity central to their practice of Christianity by addressing the social, economic, and political challenges faced by everyday Africans, many clerics, as Azikiwe observed, simply reproduced the rituals and liturgies of European and American churches. In doing so, they placed salvation in a distant afterlife instead of nurturing a vision of justice and dignity here on earth. Azikiwe’s vision of Christianity and how it should be practiced in the African society aligns more with that of African-American Baptist ministers such as Howard Thurman or Martin Luther King Jr, who rooted his non-violent activism and fight for social justice in the teachings of Jesus by centering love, forgiveness, and the intrinsic dignity of every human being. Before Azikiwe became the first president of Nigeria, Martin Luther King was invited in 1960 to Nnamdi Azikiwe’s inauguration as the first Black governor-general of Nigeria.

In addition to its failure to engage with pressing social issues, Azikiwe also criticizes the African Church for clinging to doctrines rooted in medieval traditions. Its teachings, he argues, no longer speak to the modern world nor respond to the mental and spiritual renewal demanded by the present age, which emphasizes scientific inquiry. Looking back from 2025, I am struck by the remarkable relevance of his critique of the African clergy, which may be even more pertinent today than it was in 1939. A recent conversation with my mother brought this into sharp focus.

On a gloomy summer Wednesday afternoon, I felt the need to connect with my loved ones, so I decided to call my mum to check in. Upon picking up my call, my mum informed me that she had just returned from church, where some people from an NGO had come to warn them about in vitro fertilization, commonly known as IVF. According to these individuals, children born through this procedure were more likely to become homosexual. I was stunned. Here was a legitimate use of science and human ingenuity to address infertility being perverted to propel anti-gay ideologies in the church.

A few days later, while rereading Azikiwe’s writings for this essay, I was struck by how vividly his critique still resonates. From the campaigns my mother described, to mass suicide crusades, miracle shows meant to dazzle congregations, or pastors warning Nigerian parents against letting their children study non-professional fields. The patterns Azikiwe condemned are still present with us. Today’s religious elite continues to mirror the very shortcomings Zik denounced: an absence of ethical vision, a refusal to confront real societal issues, and a tendency to keep congregants trapped in cycles of fear and superstition.

References