Between Fidelity and Freedom: The Translator in the Modern World

Between Fidelity and Freedom: The Translator in the Modern World

To many readers, translation is a neutral act, a faithful transfer of information from one language to another. As for translators, when their names are noticed at all, they are often imagined as modern-day scribes who mechanically recopy texts into a new language.

Reading or publishing a translation this way is misleading for this approach overlooks the complexity and creative demands of the translation process. As Walter Benjamin warned, a strictly literal or word-for-word translation “completely rejects the reproduction of meaning and threatens to lead directly to incomprehensibility.” Literal translations of idiomatic expressions make this incomprehensibility or confusion in translation blatant. For example, When the French word coup de foudre, “love at first sight”, gets flattened to “thunderbolt,” or bon appétit to “good appetite” instead of “enjoy your meal,” it becomes obvious that translation goes beyond replacing words across languages. If anything at all, it is an art that requires interpreting the meaning of a text in one language and reconstituting it in another. When translation is primarily seen as a process that focuses on meaning rather than literal word accuracy, the translator gains the freedom to choose words that convey both sense and effect across languages.

With such freedoms, translators may choose varying degrees of fidelity or infidelity to an original. Deborah Smith’s translation of Han Kang’s The Vegetarian shows how taking liberties can redefine a work in another language. Before the English translation appeared, many South Korean readers found the tale of a woman who believes she is turning into a tree uninteresting. Yet after The Vegetarian won the 2016 Man Booker International Prize, a new light shone on Han Kang’s story.

While some Korean critics found the translation erroneous, particularly in its handling of sentence subjects, others, such as Charse Yun, argued that the English text differs strikingly from the original in tone and voice: “amplifying Han’s spare, quiet style and embellishing it with adverbs, superlatives, and other emphatic choices”. Smith’s translation suggests that when translators are given stylistic and interpretive freedom, translation becomes a creative act that can prompt a reappraisal of the original text and even reshape how it is perceived. For example, Sun Kyoung Yoon has argued that Smith’s rendering can be read as a feminist translation that amplifies gender elements already encoded in the Korean text while also highlighting the patriarchal attributes of Korean society. Translation thus becomes a process through which the meaning of a text is stretched and expanded across languages.

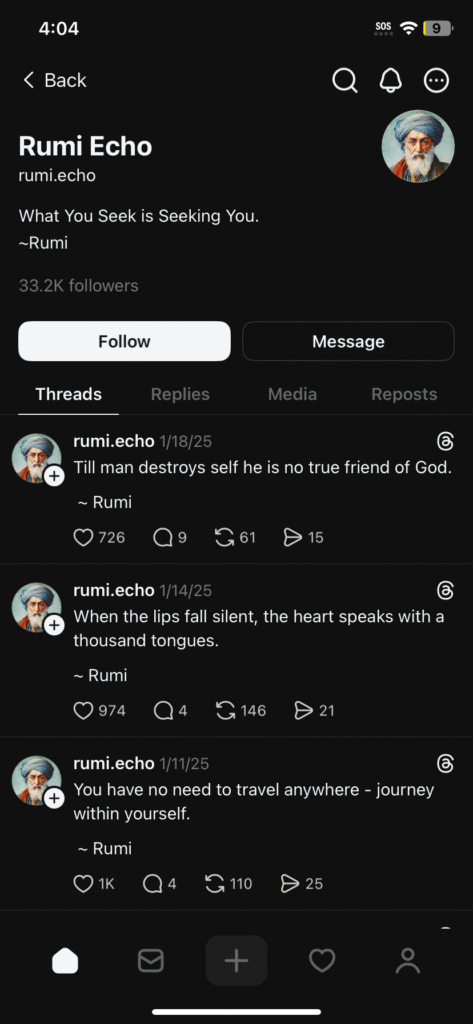

Although taking liberties in translation can yield gains, in some cases, these freedoms can also become problematic. If you follow wellness influencers or attend Islamic spiritual gatherings, chances are you’ve already encountered the poetry of the 13th-century Persian poet Rumi. His words, now shared across social media in bite-sized quotes, have inspired millions. Still, many readers don’t realize that much of the Rumi they know comes through the American poet Coleman Barks. Barks doesn’t read or write Persian, but still managed to rewrite scholarly English translations into his own poetic versions. His renditions, written in free verse instead of Rumi’s original Persian rhythms, helped make Rumi one of the best-selling poets in the United States. To imagine the weight of the choices Barks made in his translation, think of a rap song turned into plain prose; the message might stay, but the rhythm and flow disappear.

Form wasn’t the only element altered in Bark’s translation. As journalist Rozina Ali points out, Barks, like many earlier European translators, removed Islamic references from Rumi’s poetry. The result is a version of Rumi presented as “a mystic,” a secular poet whose texts fit neatly in songs by American pop artists such as Coldplay and Madonna. Even though Barks contributed to popularizing what we now accept as Rumi’s poetry, his decision to erase Islamic references reflects a broader pattern in which translators from dominant cultures reshape marginalized cultures and history. Some critics, such as Omid Safi, call the erasure of Islamic references in the English translation of Rumi’s poetry a form of “spiritual colonialism,” through which cultural context is stripped to make writings from less powerful regions of the world more palatable to foreign audiences. Rumi’s case shows how translations are sometimes altered to fit market demands.

To prevent the creative benefits of the freedom enjoyed by translators from becoming cultural erasure, we should treat translation as an act of hospitality, as Souleymane Bachir Diagne suggests. For the Senegalese philosopher, “translation should be seen as one of the responses to the consequences of linguistic domination.” Likewise, the translator, he argues, ought to cultivate an ethic of reciprocity that counters colonial asymmetries and fosters encounters in our shared humanity. In other words, translation can become a space where languages meet on equal footing, where stories cross borders without losing their roots, and where readers gain more of other worlds and not less. Alternatively, regions underrepresented in the world literature market could also set up boards or agencies that consult experts to assess how works from their countries are translated.