Hair, Wax, and Real Estate: How African Women Have Driven Local Economies and International Networks since the 1700s

Hair, Wax, and Real Estate: How African Women Have Driven Local Economies and International Networks since the 1700s

Written by Nathalie Agbessi

When I read the 2019 World Bank report, which stated that Africa has the world’s highest concentration of women entrepreneurs, my thoughts went straight to my Nigerian roommates and friends1. These ladies were simultaneously photographers, tailors, makeup artists, hairdressers, cake vendors, and university students. Upon graduation, some of them pursued salaried jobs while also launching makeup studios, hair salons, and catering businesses. Others gained admission to graduate school in the United States, Canada, or the UK, where they continued their trade and crafts as a side venture.

The experiences of my friends, now corroborated by the World Bank report, show that despite legal and regulatory barriers and weak infrastructure, women continue to lead the continent’s economic growth. Whether through the resale of haircare products, cosmetics, food, or thrifted clothing, my roommates and African women more broadly confront economic inequalities and challenges by actively participating in national and global markets.

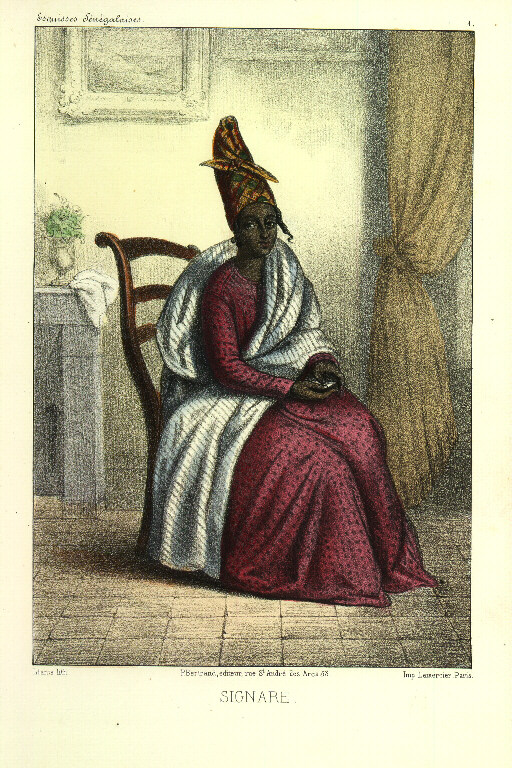

African women’s contribution to the continent’s economic development is not a recent phenomenon. As early as the 18th century, a group of female Africans, commonly known as the Signares, rose to prominence in Senegal. Around 1780, they reached the height of their influence and wealth on the African coast2.

Portrait of a signare by Abbé Boilat’s Esquisses Senegalaises

The term “Signare” originates from the Portuguese word “senhora,” meaning “madam,”. It initially referred to a married or elderly woman. However, in the Senegalese context, Signare came to signify more than marital status and denoted a woman’s social standing as a property owner. While it is often assumed that the concept of private property was introduced to Africa primarily through European colonization in the mid-to-late 19th century, the case of the Signares reveals the opposite.

House of Signare in Saint-Louis, Senegal by Carlos Reis, Flickr

The Signares emerged from unions between European traders, soldiers, and African women. Starting from the 15th century, Portuguese merchants, among the first to settle along the West African coast, began forming relationships with African women. These relationships often served both practical and strategic purposes as the men sought domestic support and needed African women’s cultural fluency to gain a foothold in regional trade. Soon enough, local expectations shifted, and these men, who were now from various European countries, were expected to marry their female partners according to Senegalese customs à la mode du pays. Paternal recognition was demanded from them, and the children born from their marriages were given the right to carry the fathers’ names. When they returned to Europe, their marriages were annulled so that the women could remarry.

We don’t know who formalized these marriage clauses, but the Signares certainly made the most of them. Unlike the Black women who were held in captivity in the Caribbean and the Americas, these Senegalese women were able to have European men recognize their children and to secure certain freedoms, privileges, and rights for them. For example, it was common for Signares to send their children to study in Europe, or even have them sail on slave ships as free men or women. In order to preserve these privileges, signares frequently hosted balls and gatherings, not just for entertainment, but also as strategic opportunities to introduce their mixed-race, or Métis, daughters to newly arrived European men.

Since these women were able to take advantage of European men’s sexual and domestic dependence, they have often been remembered in history as femmes fatales or courtesans. This distorted image was promoted by European travelers and writers, the most well-known being Pierre Loti, a successful French author who exoticized African women in Le Roman d’un spahi. In the novel, a French cavalryman named Jean Peyral describes his lover Fatou Gaye in these words: “Fatou-Gaye was quite beautiful, with her tall, wild hairstyle that gave her the appearance of a Hindu goddess dressed for a religious festival”3.

Far from being passive courtesans who exist primarily for the pleasure of European men, as portrayed in Pierre Loti’s novel, the signares, in addition to owning property and residences, also owned slaves whom they hired out to European trading companies. The slaves were often employed as sailors on ships, and their wages, paid in the form of gold and salt, were given to the Signares. Although there is little research on the Signares’ commercial activities, their influence on trade and commerce remains undeniable. For instance, in 1821, Signares Sophie and Constance Laporte married the cousins Jean-Louis Hubert Prom and Hilaire Maurel, and helped them establish what is now known as Maurel & Prom, a billion-dollar oil and gas company4. Signares who often sent their sons to Europe for education also raised a class of métis men who played active roles in local trade and education. From the mid-nineteenth century, Signare sons became forerunners of Senegal’s political elite and actively resisted the various forms of subjugation imposed on the Senegalese population by the French colonial administration.

The case of these Senegalese women is not unique in Africa. In the 20th century, the Nana Benz of Togo, for instance, much like the Signares, made strategic use of international trade by popularizing wax fabric across West Africa. Initially produced for the Indonesian market by Dutch manufacturers, this cotton textile gained widespread distribution and high value in African markets thanks to Nana Benz’s efforts. Just as the Signares distinguished themselves through their elegant and tasteful attire, the Nana Benz marked their social standing by acquiring Mercedes-Benz vehicles, which became lasting symbols of their success in Togo.

The experiences of the Nana Benz, the Signares, and even those of my friends reveal how African women have long demonstrated resilience and shaped national economies while forging links to global trade networks, in the face of persistent challenges across centuries.

References

- World Bank. Profiting from Parity: Unlocking the Potential of Women’s Businesses in Africa. World Bank, 2019. ↩︎

- Brooks, George E. “Artists’ Depictions of Senegalese Signares: Insights Concerning French Racist and Sexist Attitudes in the Nineteenth Century.” Genève-Afrique, vol. 18, no. 1, 1980, pp. 75–89. ↩︎

- Loti, Pierre. Le Roman d’un spahi. Édition présentée, établie et annotée par Bruno Vercier, Gallimard, 1992. (e-book re-issue, 2018). ↩︎

- John Ware (1807-1841): traces et mémoire d’une trajectoire goréenne.” Outre-Mers: Revue d’Histoire, nos. 386-387, 2015, pp. 159-181. ↩︎