Is the Bougival Accord France’s First Step Toward a Federation?

Is the Bougival Accord France’s First Step Toward a Federation?

By Nathalie Agbessi

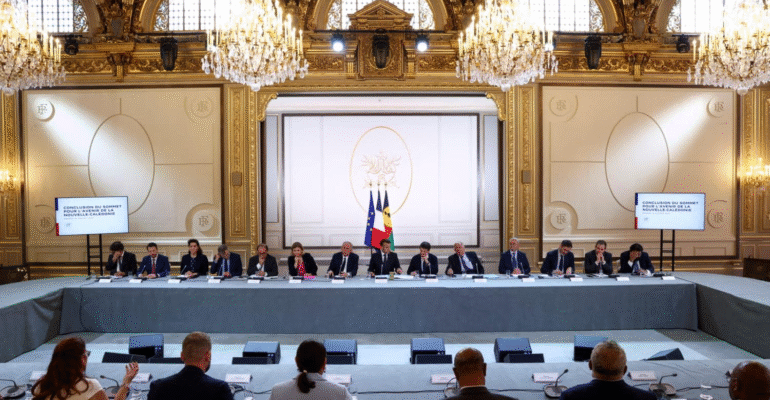

Islands are not vacation resorts. They are spaces where political futures are being tested and reimagined. Behind idyllic landscapes, sunny beaches, and turquoise-blue waters lie tidal waves of resistance, driven by islanders who have long aspired to freedom and the right to govern their affairs as they see fit. Such is the case of New Caledonia, a French Overseas territory, that, as of July 12, 2025, has been officially recognized as a state through the Bougival Accords signed in Yvelines, France.

Far from being a double-edged agreement that merely extends the reach of metropolitan power over an overseas territory under the guise of constitutional reform, I see the Bougival accord as the first step toward the realization of 20th-century Black Francophone intellectuals’ political vision. A restructured France, imagined as a transcontinental political formation called the French Union. A polity where all members, regardless of race or ethnicity, are united under Republican values. To appreciate the historical weight of the Bougival accord, to grasp how a dream nearly forgotten is resurfacing in the 21st century, we need to return to the moment when New Caledonia’s destiny became entangled with that of France.

In 1853, under the reign of Napoleon III, New Caledonia was annexed by France. Among the motives that initially led to this occupation were missionary activity, naval interests, and the desire to strengthen French presence in the Pacific area 1. In the early days of this annexation, New Caledonia was a penal colony where convicts were shipped off in large numbers to develop infrastructure and frontier settlements on the model of Australia. Slowly, toward the end of the 19th century, the island transitioned into a settler colony. In the 1940s, during the postwar decolonization movement, alongside former French colonies such as Martinique and Guyana, New Caledonia transitioned from the status of colony to that of an overseas territory commonly known as Dom Tom. At this point in history, New Caledonian society was essentially made up of the descendants of white French settlers and the indigenous Kanak population. In the 1960s, when a nickel boom drew migrants from metropolitan France, islands like Wallis and Futuna, and other French territories, the island’s population became more diverse to the point where the Indigenous Kanak population became a minority on its ancestral land. This shift in population make-up weakened the Kanak peoples’ claim to sovereignty, as migrant and settler populations began to hold the electoral majority. To date, this demographic reality continues to shape the Island’s political struggle toward self-determination.

The case of New Caledonia raises critical questions about governance in multicultural territories, as well as issues of equity and sovereignty in formerly colonized territories. Eighty years before the Bougival treaty, Lamine Senghor grappled with the same questions about the status of French overseas territories, particularly those in Africa. In his collection of essays Étapes et perspectives de l’Union française, Gueye critiqued the contradictions inherent in French Republicanism within the French Union and advocated for the people from formerly colonized territories to be subjected to the same laws and receive the same rights as the people of metropolitan France. He proposed a layered citizenship system through which French nationals would hold both French and French Union citizenship. In contrast, non‑French nationals from Asian colonies would retain their original national citizenship alongside Union citizenship 2.

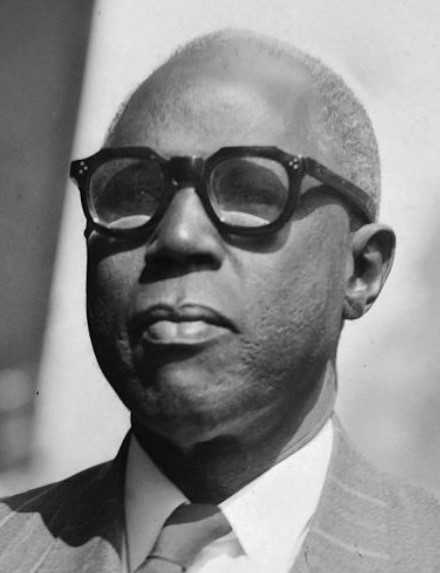

Lamine Guèye in 1946, photograph unknown, Wikipedia

For Guèye, residents of the former French colonies in West and Equatorial Africa (AOF and AEF) were French nationals with exactly the same status as those in metropolitan France. He was so committed to this principle that he erupted in outrage when Muslim pilgrims from those regions received French‑Union passports instead of full French ones. Some may dismiss Gueye as naïve, yet his plan aimed to protect Africans’ economic and social welfare while reimagining France as a polity where all are treated equally. Much like many Francophone intellectuals of the period, Gueye believed that nationalism or national independence was not necessarily the means to achieve freedom in formerly colonized territories, as it was a reactive and impractical response to years of exploitation that had left African territories without the capital, markets, and welfare infrastructure needed to sustain themselves.

The July 2025 Bougival accord, echoing Lamine Gueye’s earlier blueprint for France’s former colonies, grants New Caledonia statehood, dual nationality (Caledonian and French), and full French citizenship rights. It also acknowledges the coexistence of distinct legal systems and creates a loi fondamentale—a constitutional text that weaves together Republican, Kanak, and Oceanian ideals cherished by islanders. By formalizing customary Kanak law alongside the French civil code and regional environmental norms, the document seeks legal harmony without erasing difference. Many of its articles tackle the thorny issue of voting rights, which, as I have previously mentioned, has caused considerable tension on the island. A referendum scheduled for February 2026 will decide whether the electorate endorses the pact. Should it pass, the accord could become the opening chapter in France’s evolution from a classic nation-state toward a federation and might inspire other overseas departments such as French Guiana, Martinique, or even mainland Corsica to contemplate the same path as New Caledonia. For now, all parties remain engaged in ongoing discussions that will determine whether the agreement is ultimately adopted or set aside in the days ahead.

References

Comments (2)

Abimbola Ikumelo

A good read

Nathalie Agbessi

Thank you. I’m glad you enjoyed it.